Jerry Hunt: Four Video Translations

At the age of twelve, Jerry Hunt founded his first church, using a friend’s lithograph machine to print tracts, which he then sent to followers who responded to notices he had posted around suburban Dallas, Texas. In the pamphlets, Hunt combined lectures on alchemy with devotional exercises, simplified yoga, voodoo and the rituals of the pentagram and hexagram. Each month he answered letters from devotees who would send money to a post office box address, asking for additional informa- tion, none aware that they were dealing with just a kid. Which in a sense wasn’t true anyway. From early on Jerry Hunt seems greater than his years. in this case he meant everything he wrote, and responded to each letter with complete earnestness. The church was no scam; it was some- thing he believed in. His interests were in persuasion, and he believed he could help these people. Money had little to do with it. Already a member of every Rosicrucian order that existed at the time, he eventually attained initiate status–again, though he was underage.

He’d also shown a prodigious talent for the piano by then. Years later he studied music formally at North Texas State, and then pursued a career as a pianist, eventually experimenting with extended playing techniques, feeding into them his developed knowledge of electrical engineering and computer programming. He began building the appa- ratus for his performances when none existed to achieve the result he wanted.

It seems evident, going back to the mail order church, that his interest in music was simply an extension of the genius and devotion he held for religion, magic, alchemy, secret orders, electro-magnetic prop-

erties, the discourse of computer code. . . the vibration of the piano’s harp tapped by a row of coordinated hammers, invoking a certain combina- tion of vibrations per second, entering the air, and then the ear, altering processes in the brain. Sound is just another transmutation, yet another persuasion.

With this oversimplification we might approach the mind and art of Jerry Hunt: A general fascination with interaction within and without a system, of a presence one can’t always see, but must know, or at least believe, to exist. An orchestration of impulse. And then a million impossible specifics.

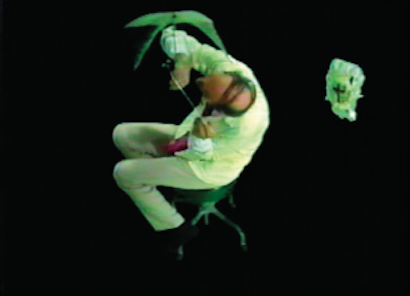

The following video stills are taken from Jerry Hunt’s Four Video Translations*–the only video release by the composer, and a late docu- ment of a remarkable, if far too brief, creative life. The stills serve as weak proxy to the actual video, maybe even irrelevant, given the sonic, choreo- graphic, and kinetic qualities offered on the video itself. Hunt’s composi- tions mutate with electronic, motion triggered sound, his intended acci- dents merging with the orchestrated score. Unpredictability was part of the event. The human ‘element’ in each of these–Hunt in solo, paired up, or reduced to a head on an Elizabethan collar, are each set against a black backdrop. Objects fly in and out of frame as his body convulses, twitches, spins, and inspects. When Hunt speaks, his prayers, invocations, non- sense, duologue, and poetic fragments seem both entirely off a point, and completely on. In the manner of the best surrealists (and religious practi- tioners), the unconscious mind of the work responds with an undeniable logic, even as it denies our identification of its surfaces.

In the first piece, Birome [zone]: plane (fixture), Hunt plays homunculus, using various objects to help‘dance’ to the music while his convulsing, entranced body plays off the ‘plane,’ responding to stimula seen and unseen, as in tropism.

Talk (slice): duplex, the second piece, is a duologue between Hunt and Rod Stasick—in essence a string of interruptions, whose length is determined by the slapping of a clave; occasionally a continuum of thought is created.

Third, in Bitom [fixture]: topogram Hunt plays a kind of sci- entist/investigator/exorcist to the subject/prisoner/victim, Michael Galbreth. Galbreth holds a metal grounding plate while Hunt probes his body for electrical conductivity with a device that simultaneously con- trols the pitch of a dominating whine, throughout.

Fourth, Transform (stream): core, severs Hunt’s head onto an Elizabethan collar, as with all the other sets, against a black backdrop. The head inquires from its platter, cocks, its eyes scan up, down, as Hunt’s vocal manipulations are answered from something from out of view.

Too weird, too transcendent of the usual and obvious, too ambiguous and too powerful to be denied a rightful place in the ongoing flux of contem- porary art, I hope the snapshots that follow are better than nothing. I can’t decide whether it is sad or fortuitous that this lifelong Texan’s most visible moment in the public sphere was probably his induction into the 1990s’ Forbidden Four. It brought him attention, as it did Karen Finley and the others. But today the reality of where it has brought us–the encampment of the religious right into a devolving squatter’s rights government, and the attendant glower on honest thought and expression–seems to have overwhelmed the initial, unintended consequence of simply turning the public on to a group of controversial artists.

And yet, for this reason alone, it is refreshing to see such a mind and its high regard for the billion impulses of potential in a single

–David Ryan, December, 2004

*(Available from oodiscs.com—catalog listing: videoO #1)