Ringer

by Glen Pourciau

Sage told stories. Whenever I saw him he had more of them to tell, and my guess was that he made them up. Should I have asked him why? I didn’t ask for fear of putting him off. I wanted to hear his latest accounts.

He’d call me. “Stories, tomorrow at eight.” I knew where we’d meet, a small café with few customers. It was understood that I was buying. On this occasion, he looked worn and had begun to grow a beard, most of it gray. I imagined he could have been telling himself stories for the past twenty-four hours and needed a listener. I said a brief hello and we shook hands. We were known at the café and the server brought us black coffee and asked if we wanted the usual. We nodded.

“Teagarden,” Sage said. “I saw him yesterday for the first time in months and was troubled by his appearance. He must have lost at least 30 pounds and looked half a foot shorter. He didn’t react when I called out his name, and as I neared him he told me to leave him alone, speaking in the raspy voice that we’d know anywhere as Teagarden’s. His clothing and teeth were in decline, which could have been a source of embarrassment to him. I struggled with the thought of offering him money and the question of whether it would have shamed or relieved him. We were near a fried-chicken franchise and I invited him for lunch. I had stories to tell, I said. He appeared to regard my invitation with suspicion, and I told him if he already had plans we could meet another time. He shook his head without looking at me, as if I were hopeless. I wondered if he’d suffered a defeat in the lawsuit he’s be tangled up in for years, and since he seemed tired I offered to drive him somewhere. He responded by demanding that I back off and turned and walked in the direction opposite to where he’d been heading, obviously in torment.”

I didn’t believe a word. I’d seen Teagarden a day or two before, and he looked the same as always and even asked about Sage, our storytelling friend, as he put it. He and Sage had been in conflict since they met in their twenties, Teagarden arguing against every sentence that emerged from Sage’s mouth.

Our server put our breakfast plates on the table, identical orders of eggs over easy, buttered wheat toast, and crispy bacon. We both took our first bite of bacon.

“I met a man recently in a bar,” Sage went on. “He stepped right up, sat on the stool next to me, never seen him before. For no apparent reason, he began speaking to me in French and German, in addition to English, saying that his three languages were those of his ancestry. He claimed he’d learned the languages as soon as he could speak because they were in his DNA, no study or lessons needed, just the gradual accumulation of vocabulary as he matured. I spoke to him in what little French I know, and based on my limited understanding he seemed to converse effortlessly and with precision. What should I have made of such a person? Should I have called him a liar? He could have studied foreign languages in school or on his own or by immersion while abroad, learning them in the same way as anyone else, but why make the absurd claim that language could reside in his DNA? I considered that maybe he merely mistook the source of his languages. Maybe his knowledge of French and German arose from a strange ability to access the collective memories of his ancestors. I asked if he could recall generations of family members walking the streets or working the fields of their native countries. He did not retain those memories, he said, only their languages had survived in him. His refusal to embellish his ancestral memories bolstered my estimation of his sincerity. He continued to address me, mostly in German, and I understood nothing of what he said, except words I’d learned from World War II movies. He didn’t care at all that I could not understand him and I had an inkling he may have preferred it that way. He never asked a single question about me, and I did not interrupt with any of my own stories, supposing from his self-involved manner he’d have no interest in hearing them.”

The server came to refill our coffees, and Sage voiced a brief complaint that his eggs were slightly overcooked. I took a breath, waiting.

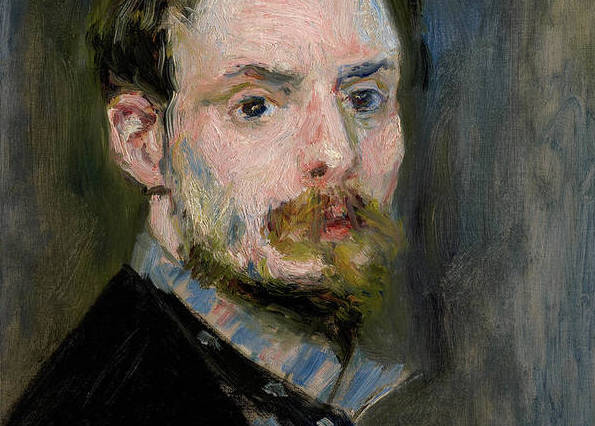

“At a recent art show,” Sage told me, chewing, “I ran into someone who struck me as familiar, a gaunt man with thinning hair and a wispy beard. I approached and asked if we’d ever met. He had no recall of our meeting if we had, he said, but many people commented he looked familiar. He then gave me the reason. Staring into my eyes, he asserted that he was a dead ringer for a famous self-portrait of the painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. He pulled out his wallet, which contained a small printed copy of this portrait. He unfolded it and, with a flourish, held the portrait in front of my face, asking if I could tell the difference between it and him. I conceded I couldn’t. He showed me his driver’s license to prove his first name was Pierre. I stared back at him, fearing further elaborations while at the same time wanting to hear them. Pierre told me he too was a painter. His mother was French, studied art, and painted for her entire lifetime, her work still hanging in several museums. I asked what he was getting at. One interpretation, he replied, was that he was a distant relative of the great painter and another was that he was the reincarnation of the man himself. Farfetched? he asked me. How else can you explain a dead ringer? Many others in the art world, in which he had connections, had admitted to him that his eerie resemblance to Renoir strained credibility. How many people have ever looked exactly alike? he demanded I tell him. Skeptical about reincarnation? What about the Dalai Lama? He is accepted as a multi-century reincarnated person with special capabilities. If he can be reincarnated, why can’t the same be true of other people? Have you ever heard anyone say the Dalai Lama was a phony? he asked. He wanted me to embrace him as the new Pierre-Auguste Renoir, though no one as far as I know has ever maintained that all Dalai Lamas have looked alike. I had to admit the similarities between this Pierre and the printed portrait were striking, perhaps due to some effort by him with his hair, beard, and facial expression. But I had no basis for calling him an impostor and acknowledged I could not prove him wrong.”

He let the story hang in silence and pushed his plate away, clearing his throat. I said nothing, unsure whether he’d met this Renoir look-alike. Were his stories in some sense partly true? But which parts and in what sense? According to him, unusual encounters followed him wherever he went, and I could not believe they’d all happened as he stated.

“One more,” he said, raising his index finger. “I called someone to my house to make minor repairs after reading an ad in the newspaper. He arrived on time and introduced himself as Plural. Surprised, I asked if his parents had given him that name or if he’d changed it. He looked ruffled by the question at first, but seeing I had no sarcastic intent he answered. His parents had named him Plural and they’d raised him with the idea that his birth gender should not limit his choice of gender identity. His mother is a birth man named Lulu, he told me, and his father is a birth woman named Lou. I didn’t ask him his birth gender, but he appeared to be a man, I would guess in his early twenties. I didn’t ask if he was adopted or if his parents were still married. I’d stuck my nose in far enough. I thanked him for what he’d shared of his history, and he got to work on the repairs. You may be asking yourself why I would dream up the story of Plural. Could I be attempting social commentary or do I intend to characterize his family as odd? I have no specific purpose in telling you of these people other than to share what they said to me. I assure you they are out there, and it frustrates me not to know the stories that lie hidden within their words. I see questions in your face, and your puzzlement signals the reason I called. You are curious just as I am, and though I can understand if you don’t completely believe me you’re able to suspend enough doubt to consider the lives behind the stories. Is Teagarden right to dismiss them? Would I see questions in his face seeking resolution? I think not, but his anger could indicate that my stories reach him in ways he can’t admit to himself. Thank you for breakfast and for listening to me. I enjoyed our conversation. I’ll call again when I have more.”

Glen Pourciau’s third story collection, Getaway, is forthcoming from Four Way Books in 2021. His stories have been published by AGNI Online, Epoch, failbetter, Green Mountains Review, New England Review, New World Writing, The Paris Review, The Rupture, Witness, and others.