There and Back

Maggie Maize

Mama and I wanted to see the country. We made the 3,409-mile train trip from Emeryville, California to Savannah, Georgia, where I’d start Savannah College of Art and Design and hopefully “figure it out.”

| California Zephyr | Emeryville — Chicago | 51 hours 40 minutes * |

| Capital Limited | Chicago — D.C. | 17 hours 25 minutes * |

| Palmetto | D.C. — Savannah | 13 hours 8 minutes * |

*delays not included

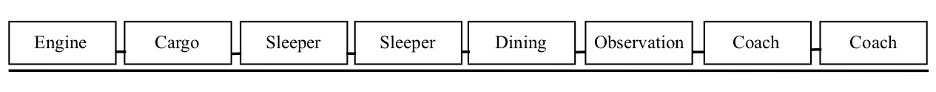

The double-decker Zephyr slowed to a crawl through the Sierras. We were behind schedule before we left California. Private freight companies owned most of the tracks and controlled dispatching, so we’d stop to let them pass. This order was a much different picture than pre-boarding. Turns out that Amtrak functioned on trust and people who disliked flying. No metal detectors. No pat-downs. No liquid limits. Only half-assed ID checks.

That evening we rattled 70+ mph through the Great Basin. Passenger trains usually use stretch breaking to increase tension between cars for a smoother ride. That wasn’t the case that night. Perhaps the engineer assumed we were asleep and wouldn’t notice sharp jolts. Our car jostled; beds pitched. It’s difficult falling asleep with your fight-or-flight senses excited. Somehow the safety straps latched to the ceiling weren’t comforting either.

I’d been pushing the tragic stories about derailed speeding trains from my mind. Then Mama said, “I had an earthquake dream.” That gave me something new to think about: sweet California, years overdue for a catastrophic earthquake.

When daylight came, I used clues to “see” beyond the curated views out the window. After all, we passengers couldn’t see the tracks or crossings ahead. I learned to rely on our horn and speed to anticipate towns or traffic. Mama navigated a map, picked names off of signs, tracked landmarks and angles of roads. It’s satisfying being on the other side of the gates, enjoying lunch while all those cars wait for you to pass.

Mealtimes were structured: 6:30-10 a.m.; 11:30-3 p.m.; 5-9:30 p.m. Servers lumped together four passengers into booths. The kitchen was below. That’s where they thawed, cooked, and plated the carb-heavy meals. Salads and veggie burgers—the only variants from yellow food or steak—sold out first, so we ate early.

This car is where you get to practice your train-pitch, a repeatable story that gives fellow passengers an idea of who you are. A train-pitch answers the go-to questions: “Where are you going? Why there? Where are you coming from? What do you do?” The last question stressed me out. I’d been wandering for the past two years. Picking anything felt misleading.

One night we ate dinner with a down-to-earth Virginian couple on their way to Denver. The woman was a weaver. The man was a lawyer who appreciated art. He once offered a re-offender a deal to move somewhere touristy “like San Diego” and paint motorcycle gas-tanks. The offender passed it up.

Near the end of the story, a British accent distracted me. The young man sat down across the aisle and told his strangers that he was a writer. Everyone laughed at his theatrically delivered stories. A few minutes later, his tablemates fell into hushed whispers. He asked his strangers how to approach me and if he should with my mom there. I ordered my interests, so I’d be ready if he got around to asking. He didn’t ask, though. He’d probably already heard me tell the Virginian couple the cluttered version.

The long days were suitable for thinking and writing. How many houses had we passed? What an intrusion—the blaring horn in the standard sequence: long, long, short, long. And this was a single route, a single train. A plane doesn’t have to be very high up for people to disappear, for land to become a patchwork. The train’s wake was personal.

I desired some of the simple living we saw. All the experiences I couldn’t live overwhelmed me. One life, that’s it. Parked, staring at tiny farmhouses while a freighter passed us, I believed I could part with technology altogether and learn what life was supposed to be.

Some days, hovering in the bathroom and walking to the observation car was the extent of our exercise. Of course, you don’t take a cross-country train expecting tremendous activity. But by Colorado, Mama and I were desperate for fresh air. Most stops weren’t long enough to get off. During fuel breaks, we got ten or fifteen minutes to pace the platform and hold our breath through crew members’ cigarette smoke.

It didn’t matter which passenger car we boarded. The key was getting back on since it was the only train of the day. When the thrill faded, I mourned those who stayed off and continued their stories that I’d never converge with again. Dramatic, yes, but also true.

“I’ve only been trying to get you alone for the past two days,” the Brit said. He said it like I’d used great wit to escape him last time. Mama was back in the room, taking a nap, and it probably was the first time we were apart.

The twenty-three-year-old worked for some magazine in Chicago. He was returning to the city with travel articles. He admitted to stretching stories for interest. My weirdo-meter urged me to walk away, but maybe he repeated everyone’s name too often. I also laughed off his persistent offers to buy my sweater.

“So, Maggie,” he said, “tell me your story.”

My still-messy train-pitch came out so flat that he changed the story right in front of me. He took notes in a pocket-sized journal, across from mine, but wouldn’t let me see what he wrote. I confessed how disoriented I felt lately, how so much felt unattainable. “My words” likely made an excellent quote for his fabricated article. He joked that my interest in fiction meant I wrote smutty fanfiction. I should’ve laughed because my objection only emboldened him to detail his intimate relationships. I squirmed, and he beamed. I left him in the booth; he asked to stay in contact.

We arrived in Chicago six hours late and had to scurry to our connection. Tingly sadness sunk in once we were settled. I thought it was because I’d overshared. Little did I know the feeling would pulse back (even years later) each time someone said, “not to worry,” and I’d “figure things out.”

The observation car was built for eavesdropping. Complaints buzzed in this shared space. “There’s no wi-fi.” “Why are we late?” “The bathroom reeks.” “My seatmate is spilling onto my armrest.” A young man in a stretched-out T-shirt said into his phone, “I paid $8 for a mini-bar size of Jack Daniel’s.” His unfocused gaze slid over the rusty factory, glowing in the sunset. We’d be late to his stop in Toledo, Ohio. He hung up then struck up a conversation with a neighbor about his $8 shot.

In D.C., we got on the Palmetto, which felt like a dated airplane with its blasé curtains and faded warning signs. This train was single story. Our roomette had a toilet right beside the sliding door but had little privacy thanks to the drape’s age-worn Velcro. Flop the toilet seat down—that was the step to my bunk.

Hot air slurped through the doors as passengers moved between cars. Then we arrived in Savannah. We’d become yet another set of passengers let off before the train’s final destination. The trip felt incomplete, and I thought about the train for the whole quarter. I longed to get back on. So, in November after finals, Mama and I took the 3,409-mile trip back to California.

I recognized the houses and farms I’d fallen in love with back in August. A harsh freeze had blanched most everything dead. In Virginia, an Amish man talked about organic food with an educator. They discussed the corruption of companies claiming to be non-GMO and selling “organic” farmers genetically modified seeds.

A girl about my age joined the conversation, saying she was a religion major. She asked the man why the Amish shun some people from their community.

“They’re excluded from activities like church if they don’t try to live our way,” he said. “It’s that harsh because we want them to repent and reenter the community.” He backed his words with Bible verses. I wonder if the man was satisfied with his own train-pitch.

Then on the Zephyr, there were young farmers headed to Omaha, Nebraska. They wore dirty boots and pointed to fields saying, “They missed harvest by a week.”

I also met Kat, an 18-year-old in the observation car. Her mousy hair straggled over her shoulders. She’d bought a coach ticket, but the windowed car was where she spent most of her time. She boarded in Denver and was returning to rural Northern California after a spontaneous trip to Arkansas, where she was scoping out land. My anxiety seemed novice compared to Kat’s honed paranoia.

She and her boyfriend planned to move to Arkansas, use her solar energy knowledge to go off the grid in the mountains. This prep was for when the government crumbles, technology backfires and inevitably crashes.

Kat and I watercolored at a table, and the train’s wheels squealed long songs around bends. She set down her brush until her storytelling high faded. She’d pick it up, set it back down. This continued for a couple of hours. My train-pitch was no better than last time. For some reason, I told her about my confusion. Much like the Brit and everyone else who I’d told, though, Kat changed the subject. Why did it keep slipping out on the train? I wanted dates when I’d “figure it out.”

Mama eventually came looking for me. I wanted to give her a warning signal, but she was a better audience than I. Kat even backtracked part of her lizard-Illuminati conspiracy for Mama’s reaction.

Kat spoke in absolutes—even if she couldn’t explain. I agreed when she said we’re too dependent on technology, the government knows too much, and money comes and goes. My responses contributed little to the conversation. That’s the way she liked it, or so I thought.

“You know that bad feeling you get sometimes?” Kat said, over her sopping wet painting. Now she was talking to me. “Always trust that bad feeling.”

I’ve thought about Kat a lot since then. I wish I’d asked her how to decipher vague worries from legitimate warnings. California, too, had browned in the early freeze, and the marshland along the Bay was stagnant. The last few hours stretched long. I was ready by the time we arrived at our stop, the last stop. We disembarked with the remaining passengers, and things were still uncertain.

Maggie Maize holds a BFA in writing from Savannah College of Art and Design. Her writing has appeared in Savannah Magazine, Perhappened Mag, Funicular Magazine, and Sledgehammer Lit. She lives in Northern California.